Rest of today – partly sunny with highs in the upper 50s.

Tag Archives: el nino

NYC Weekend Weather – Dec 04, 2015

A quite and mild weekend is in store for the region with high pressure in control of the weather throughout the period. Temperatures should climb steadily as winds shift and persist from the southwest. We could see high temperatures near 60ºF by Sunday.

Rest of today – clear to mostly sunny, with highs around 50.

Saturday – sunny, with high temperatures in the low-50s.

Sunday – milder, and sunny again with high temperatures in the upper-50s to near 60ºF.

Monday – clouds look to be increasing on Monday with a storm system approaching from the south expected to pass on Tuesday. Temperatures will be cooler in the mid-50s.

Seasonal Climate Outlooks

As we are entering into the winter, it’s worth looking ahead at what the seasonal climate out looks are from the Climate Prediction Center.

Drought conditions are expected to improve over many areas of the nation, and the persistent moderate drought in our region is forecast to end.

Temperature and precipitation are forecast to be above normal for the region. As you’ll note from the images below, some fairly significant deviations from normal are expected across large portions of the United States, due in large part to the effects of a strong El Niño that’s been gripping the Eastern and Central Pacific for months now.

The chart below shows you the sea surface temperature anomalies for the Pacific – notice that a large swathe of the equatorial Pacific from about the international date line east is experiencing extremely warm temperatures for this time of year – a full 5ºC above normal in large areas. This is why climate forecasters can be more confident than usual in their outlooks for temperature and precipitation this season.

Hurricane Iselle – Tropical Update

I haven’t been active on this blog the past couple of weeks as I’ve been in Costa Rica, however, the unfolding situation with Hurricane Iselle warrants a posting. I’ve observed Iselle as it formed from a tropical wave and then a tropical depression along the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone off of the coast of Central America where I’m currently staying. Now, Iselle is closing in on the Hawaiian Islands and is set to make landfall on the Big Island this evening.

Despite the fact that the Hawaiian Islands lie near an active area for tropical cyclones, they are rarely impacted, in part due to the sheer vastness of open ocean versus the relatively small land area of the islands. During most years, a semi-permanent high pressure area that resides near the Islands also precludes the formation, strengthening, and penetration of cyclones into the region. This changes dramatically when El Nino conditions prevail, as they seem to be currently. Iselle will be the first landfalling hurricane to affect the Hawaiian Islands in 22 years since the devastating Hurricane Iniki of 1992. Fortunately, Iselle will be making landfall as a much weaker storm than Iniki, but regardless, it will still pack a serious punch.

Track Forecast

With less than 24 hours before landfall, the forecast track for Iselle is essentially zeroed in. The official track forecast cone has Iselle hitting the Big Island straight on. The center of the current forecast track envelope, should it hold up, has Iselle potentially making a direct hit on the eastern portion of the Big Island, with the eye of the storm skirting just south or perhaps directly over the Hilo area. I would hope for a northward deviation of this track, as this would spare the region from the strongest quadrant of the storm’s winds and waves (in the northern hemisphere, the strongest quadrant of a cyclonic storm is generally the northeastern quadrant). In the case of Iselle, due to its forecast west-northwest motion, the strongest quadrant should actually be the northwest, since the forward speed of the storm is added to the winds in that area.

After making landfall on the Big Island, Iselle is forecast to move to the south of the rest of the islands, passing closest to Maui. Because of uncertainty in the track forecast, it is entirely possible that Iselle could end up making multiple landfalls on different islands. However, I would anticipate these subsequent landfalls to be less serious in nature as Iselle should weaken substantially due to the influence of interaction with the mountainous terrain of the Big Island as well as increasing vertical wind shear from the north and west. There could still be some damaging storm surge and high winds in the other Hawaiian Islands, especially if the center of Iselle passes to the south of them.

Intensity Forecast

Iselle has been stubbornly persistent in maintaining minimal Category 1 status. Forecast models have been giving conflicting signals as to whether Iselle will be impacted by increased wind shear. Forecasters had not anticipated that Iselle would enter into a col between two high pressure centers, essentially an area of very low wind shear, think of it as a calm spot between two swirling eddies. Different forecast models are providing two divergent scenarios: (1) that Iselle continues to move in tandem with the col, allowing it to maintain current strength, or (2) Iselle leaves the col and experiences much higher wind shear.

No matter what, Iselle will be making landfall on the Big Island as either a minimal Category 1 hurricane or a very strong tropical storm. The real impacts of either scenario will be hardly discernible. Wind over the Big Island should pick up substantially this afternoon and evening first from the northeast, then north, and then switching to the south and southeast overnight. Sustained tropical storm force winds in the range of 50-65mph are expected depending on the specific locale. Wind gusts of up to 90mph are also possible in some locations. Offshore waves will build from 6 feet to as high as 31 feet closer to the center of the eye. I hope all people on the islands are making adequate preparations. Wind speeds as high as the ones forecast could easily shred even a decently well constructed roof. I’m not sure if the local government has issued evacuation orders, but if so, I hope all citizens of Hawaii will heed the call and take every necessary precaution to secure life and property. Let’s hope this Iselle weakens some more before it makes landfall.

Notes

In contrast to the Atlantic Hurricane Season thus far, this year’s Pacific Hurricane Season has been quite active, in part due to the influence of anomalously warm sea surface temperatures over the Eastern Pacific. These temperatures are indicative of what could be the start of an El Nino event. Hurricane Iniki also formed during a very strong El Nino event.

2014 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook – Jun 2, 2014

Yesterday marked the official start to the 2014 Atlantic Hurricane season (June 1 – November 30), so this is as good a day as any to talk about the forecast for this season. The graphic below shows the National Hurricane Center’s official 2014 Hurricane Season Outlook that was released last month. This forecast is probabilistic, i.e. it gives a range of numbers and chances that this season will either exceed or fall below the forecast total.

Explanation

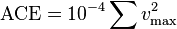

In the NHC’s parlance, Named Storms refers to tropical or subtropical storms that produce sustained winds in excess of 39mph (this is the criteria for a tropical or subtropical storm) at any point in their life cycle. Hurricanes refer to the named storms that end up producing sustained winds in excess of 74mph, and Major Hurricanes refer to hurricanes that make it to Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson classification scale. Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) is a rough measure for the overall intensity of a tropical cyclone and is calculated as follows:

The ACE of a season is calculated by summing the squares of the estimated maximum sustained velocity of every active tropical storm (wind speed 35 knots (65 km/h) or higher), at six-hour intervals. Since the calculation is sensitive to the starting point of the six-hour intervals, the convention is to use 0000, 0600, 1200, and 1800 UTC. If any storms of a season happen to cross years, the storm’s ACE counts for the previous year.[2] The numbers are usually divided by 10,000 to make them more manageable. The unit of ACE is 104kn2, and for use as an index the unit is assumed. Thus:

where vmax is estimated sustained wind speed in knots. (Source – Wikipedia)

Hence, a high ACE number corresponds to a very intense storm or storm(s).

Outlook

As you can see from the above image, the NHC is calling for a normal to slightly below normal season for the Atlantic with 8-13 named storms, 3-6 hurricanes, and 1-2 major hurricanes. Despite the fact that the forecast calls for a normal to below normal season, it only takes one landfalling hurricane or major hurricane to inflict serious damage to a coastal area. Even with just tropical storms, huge amounts of rain can fall leading to major flooding.

El Niño’s Impact

One of the reasons why the forecast is calling for a normal to below normal season is that it appears an El Niño event is initiating and forecast to increase in intensity. El Niño refers to a phenomenon that occurs when the ocean surface of the Eastern Pacific Ocean becomes abnormally warm (La Niña refers to the opposite effect, when the Eastern Pacific cools abnormally).

This anomalous warming of the Eastern Pacific leads to all sorts of global climate impacts. Among these is a noticeable decrease in the incidence of Atlantic hurricanes, and an increase in the number of Eastern Pacific hurricanes. In fact, you can see in the same outlook, NHC is calling for a near normal to above normal hurricane season for both the Eastern and Central Pacific. The reason behind this is simple: hurricanes feed on heat to grow, so the warmer the water below a storm, the greater the potential for that storm to grow.

As you can see from the map above, there is a region of abnormally warm sea surface temperatures extending west into the Eastern Pacific from the coast of Ecuador and Peru (yellow & orange). At the same time, there is a large area of much cooler than normal sea surface temperatures extending from the west coast of Africa into the Central Atlantic (light and dark blue). Incidentally, these cool temperatures off the coast of Africa are in a region that is notable for spawning some of the strongest hurricanes, the Cape Verde type hurricane. Clearly, if this temperature anomaly keeps up, it will serve to inhibit the formation of tropical storms and hurricanes in that region.